Most people in science and engineering professions are very familiar with the concept of optimization.

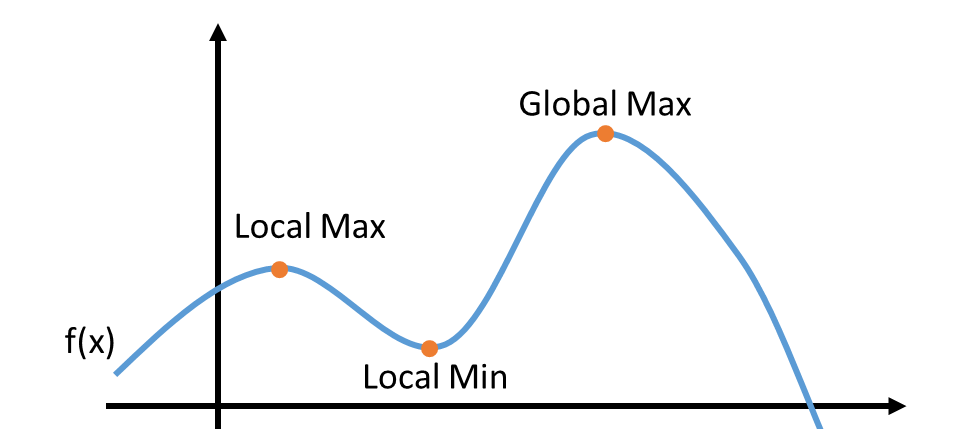

We are also familiar with the traps of local versus global optimization and how to protect our code and models against those traps. However, we frequently fail to realize that the same concepts can be applied to our careers.

The Trap

It’s usually not hard to find what’s required to progress on your current job. You might have access to “career stage profile” documents that describe the characteristics of that job for different levels and what’s required to move from one level to another. Your colleagues or your manager can tell you what it takes to get promoted. Getting promoted is a good thing: it will give you a better salary and sometimes an expanded scope that will allow you to have opportunities to grow even further.

I had many career conversations in my tenure, and in a large proportion of cases, “getting promoted on the job I currently hold” is not a typical lifelong objective, but it’s typically an objective that people have a plan for. On the other hand, people frequently tell me about major goals/objectives (change professions, open their own company, get a Ph.D., etc.) for which they don’t have an action plan.

It’s like their algorithm is stuck near a local maxima (in this text, optimizing will mean maximizing) and the only thing they can see is the short-term objective, so they can only trace paths to get to the local maxima.

Eventually, people reach a local maxima and realize it’s not their global objective. They may not know what their global objective is, they just know “it’s not this”. Interestingly, the way that people solve that problem is not that different from what an algorithm would do if it realized it got stuck in a local maxima: take a big step, and start again from someplace else.

A simple fix

The more you know about the neighborhood about your global maxima, the easier it will be go trace a path to get there. Even if the path is not exact, at least you can tell whether you’re getting closer or further away from that goal.

Career coaches (and good managers) keep asking you about your “global objective”. By learning more about it, they can tell you more the path to get there, or find someone that can. Over time, you may accumulate enough information to make a better move when you decide to.

The multi-armed bandit

The hardest problem to solve in career optimization is lack of information. People may have some general idea of where they want to go, but usually not much. For example, I commonly hear people saying that they want to become managers, but after just a few questions I realize that they don’t really know what that means and whether they actually want that.

One way to maximize happiness under incomplete information is to explore several different things, and once you find what makes you happy, then you exploit it (although “exploit” is a somewhat aggressive word in English, it’s actually the technical term), getting as much happiness as you can from it. There are algorithms to find a good balance between exploration and exploitation. One example is the “multi-armed bandit”.

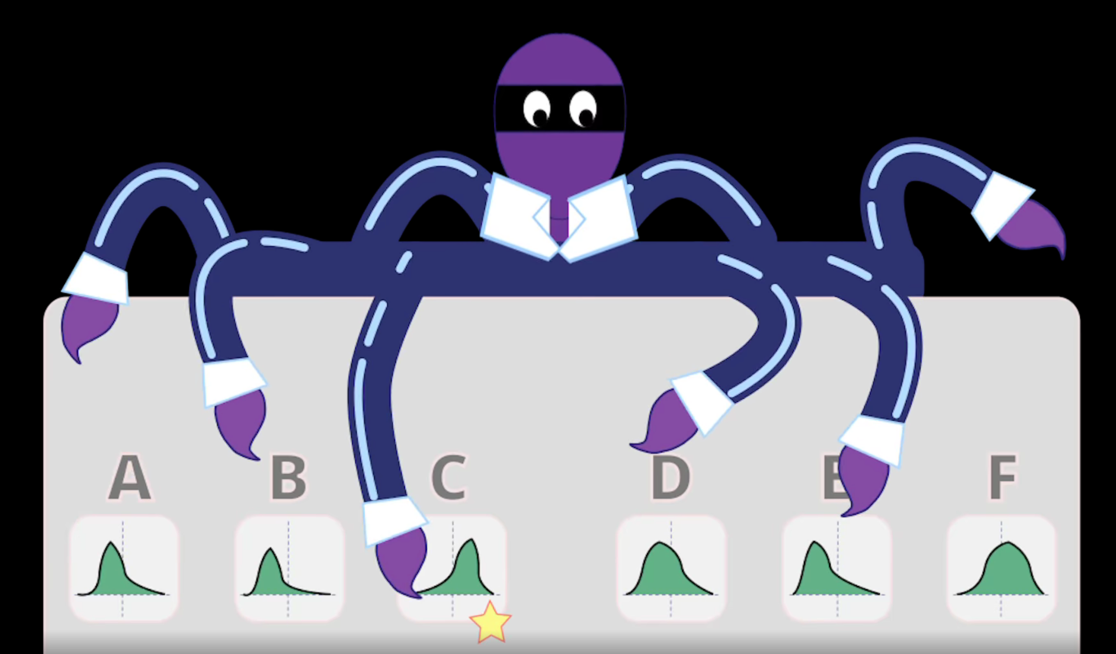

The concept comes from slot machines in casinos. Because a slot machine has one lever that people pull to activate it and people usually lose money on it, it’s called an “one-armed bandit”.

Imagine a slot machine that has multiple levers, therefore a “multi-armed bandit”. When pulled, each lever gives a prize based on a statistical distribution that is unknown to the player. You pull the first lever and get $100. Should you pull the same lever again or switch? Maybe one of the other levers has a constant payoff of $1,000. Maybe that lever you just pulled is actually the best one.

Without knowing the distributions, you can’t know the optimal action to take. In real life, not only one doesn’t know the distributions, but the distributions for each lever can change over time. If that was not complicated enough, you also have infinite levers to choose from. Nobody said it was supposed to be easy.

The multi-armed bandit problem doesn’t have a general optimal solution, but has several strategies that achieve approximate solutions. It is a classical reinforcement learning problem.

Many strategies are very simple “epsilon” strategies, for which one decides a proportion epsilon (between 0 and 1) of exploration (trying to figure out the distributions of the available actions), and the remainder of the time is used for exploitation (performing the action that is expected to yield the best results).

In career conversations, I always suggest that people take the time to explore new things, especially things that are in the (conceptual) neighborhood of what they think they want. Because I’m older than the average tech person, they may think this is some form of ancient wisdom, but I’m just pointing them towards a classical (and somewhat modern) reinforcement learning algorithm.

That’s using data science in production.