These days, calling someone a “Luddite” is an insult, a little bit like “boomer”. But the original Luddites were not exactly afraid of technology — they were afraid of losing their jobs to technology. They were skilled workers who saw their livelihoods threatened by machines that could do their jobs faster and cheaper. Sounds familiar?

Croppers

A central figure of the Luddite movement was the “cropper”, a skilled worker who used large shears to finish cloth pieces. The shears were heavy (40 lbs) and unwieldly, and using them well was tiring and painful, requiring a lot of training. Over time, croppers developed a large callus on their forearm (called a saddle), and it was said at the time that “you could tell a cropper by his saddle”.

A good finish could mean the difference between a piece of cloth that would sell for a high price and one that would need to be thrown away. Given their importance, the training requirements, and the physical toll of the job, croppers were well-paid, high-status workers. But then, in the early 1800s, some machines were invented that could do the job of the croppers as well as the croppers themselves, but also faster and cheaper.

The conversation below was reported by the nineteenth century historian Frank Peel, who recorded oral stories handed down over generations in his book The Rising of the Luddites.

The Conversation

In a cropping shop, a group of men are talking after work. Most of the men are croppers, and recently started forming gangs to smash the new machines. One of men is John Booth, a nineteen-year-old apprentice saddle maker, the son of a clergyman with the Church of England. Since he is not a cropper, he’s not directly affected by the new machines. Not yet, anyway.

“Would it not be better,” asks Booth, “to reason with them rather than infuriate them by destroying their machines?”

“Reason with them!?,” says one of the croppers, “We might as well reason with a stone!”

The cropper is named George Mellor, and he’s the local leader of a masked marauding gang that destroys the machines that are replacing workers. Mellor is still working for now, but he knows that he can’t compete with the machines. He and his fellow croppers can see that the skill they’ve spent years perfecting is soon to be rendered worthless.

Booth clearly thought this out, and says that “being a cropper is hard work, and painful too, until you develop that hard, calloused skin on the wrist. But have you seen those machines in action? You just have to set up the cloth and keep an eye on them. They take away all of that hard, painful work. Seen like that, the machinery is a thing of beauty.”

Booth continues, “I quite agree with you about the problem, and respect the harm your livelihood suffers from the machinery. But such a machine might be man’s chief blessing instead of his curse. You can’t say the machine itself is evil, that’s absurd! No, the problem is that the mill owner gets all the benefits. If society was differently constituted, if those benefits were fairly shared out…”

Mellor interrupts him. “If, if, if…” he says. “What’s the use of such sermons as thine to starving men?”

England is at war with Napoleon’s France, and the war has disrupted trade. Nobody’s hiring, and the price of food has shot up. Another cropper joins in the conversation. He tells how he went to see a former workmate, a cropper who lost his job. He can’t find work. The man’s been struggling to afford to eat, and now his wife has died. “There she lay on the bed, poor thing, skin and bone.”

It’s hard for John Booth to argue with that. He is sure that the machines would be a blessing if society were differently constituted. On the other hand, he also knows that his cropper friends are right. There’s no chance of reorganizing society at present, and there’s no comfort in imagining a different societal organization when you are starving to death.

“What can I say?” asks Booth.

“Say you’ll join us,” says Mellor.

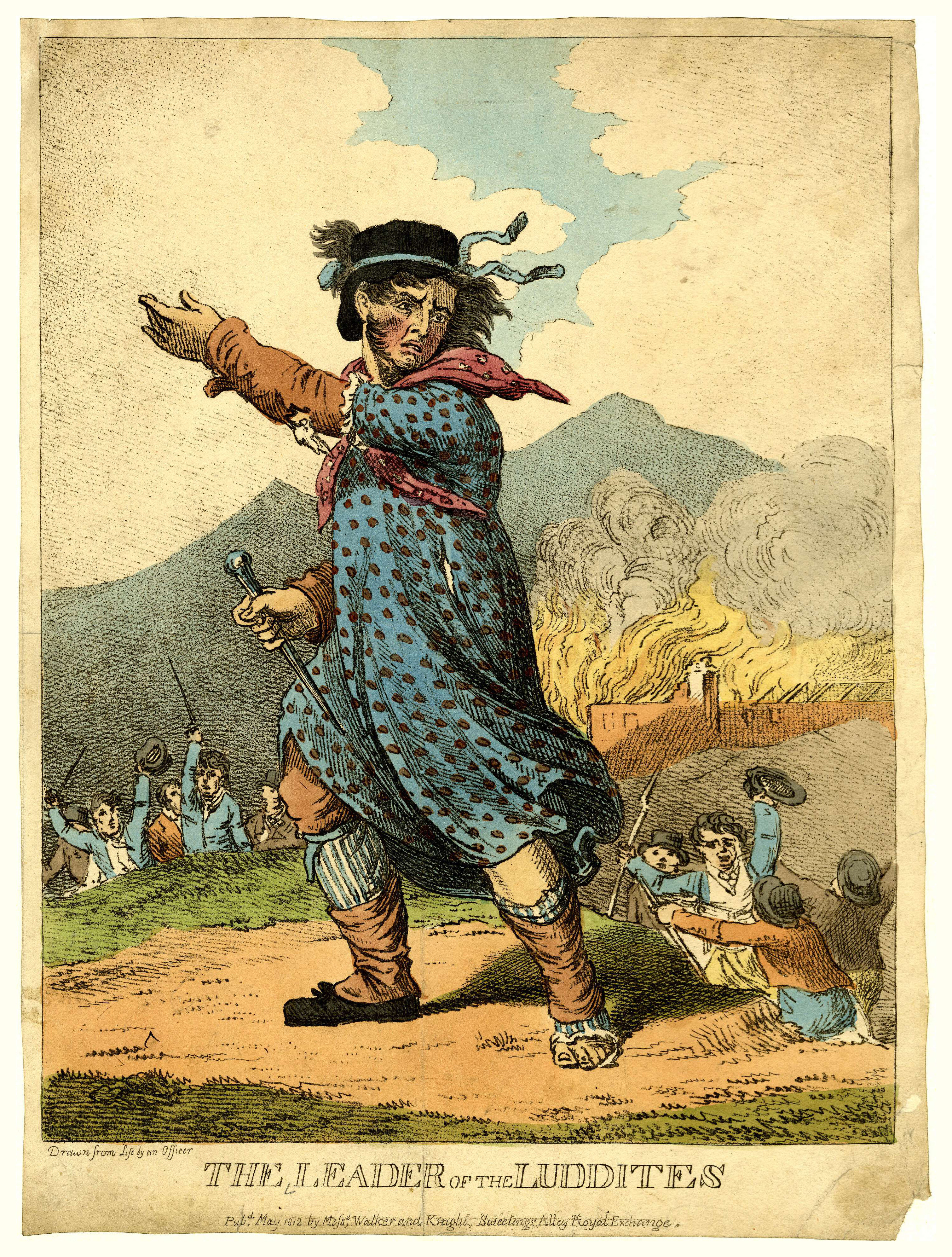

The Luddites and General Ludd

The gangs were not a single, unified group. They were a loose collection of people who were angry at the new machines and the mill owners who were using them.

There was a local story that a young weaving apprentice named Ned Ludd smashed two machines in a fit of rage. When gangs started smashing machines, the story goes, instead of snitching on them, the other workers would say that “Ned Ludd did it”. Over time, the gangs incorporated that legend, and said that they were acting on behalf of General Ludd. Incidentally, General Ludd was supposed to live in Sherwood Forest, same as Robin Hood. Before striking, the gangs would usually send letters to the mill owners, ordering them to stop using the machines otherwise they would be smashed. The letters were signed “General Ludd”. The followers started to be called Luddites.

For a while, the Luddites were successful. Mill owners were concerned, and some stopped using machines. However, a few mill owners held out. One of the holdouts was William Cartwright, the owner of Rawfolds Mill. On April 11th, 1812, more than than one hundred Luddites gathered at the Dumb Steeple, still a landmark near Mirfield, in Yorkshire. At the dead of night, they marched on Rawfolds Mill. But Cartwright was ready for them. The mill was fortified and soldiers were stationed there. The Luddites were beaten off and two of them were killed.

One the dead was the nineteen-year old John Booth, the young apprentice saddle maker who had been trying to reason with the croppers. Legend says that before Booth died, a reverend tried to extract from him the name of the local leader of the Luddites under the seal of the confessional.

Booth asked the reverend, “Can you keep a secret?” The reverend said that he could. “So can I,” said Booth, and died.

The Mill Owner’s Problem

It’s easy to see the mill owners as the villains of the story. They were the ones who were buying and using the machines that were putting the croppers out of work. They were the ones that put soldiers to fight against the common man. But the mill owners had a problem too. Machines were making the production of cloth much cheaper. If they didn’t use the machines, they would be outcompeted by other mill owners who did.

Even if the Luddites were successful across the whole kingdom of England, a different country could organize itself to start using the machines. If that happened, the mill owners would still go out of business, and all of their workers would be out of work, including the croppers.

The Luddites and the AI Revolution

John Booth’s argument was on point. Centuries later, the economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson wrote the book Power and Progress, in which the central argument is not very different from the one in John Booth’s conversation. “Progress depends on the choices we make about technology. New ways of organizing production and communication can either serve the narrow interests of an elite or become the foundation for widespread prosperity”.

In the book, they provide several other examples spanning over a thousand years. The examples include resource allocations that did not work, like the agricultural innovations in the middle ages that led to larger and more opulent cathedrals. They also include allocations that did work, like the assembly automation in the 20th century that led to the rise of the middle class and the increased prosperity of the United States post World War II.

Now, with AI, we again have a technology that can do the job of many workers faster and cheaper. Will we, as a society, do better this time?

What the future holds

It seems inevitable that AI will be incorporated more and more in the workplace and in day-to-day life, to the extent that it may be pointless to try to stop it. Several countries already have defined strategies to incorporate AI in their economies, so even if a fight against AI is successful in one country, that victory may translate into a much bigger loss. Avoiding AI is unlikely to be a long-term winning strategy.

When people ask me about AI, I frequently tell them to start using it in their day-to-day, to understand its limitations and its potential. I suggest that the get a suscription like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Bing Copilot and attempt to use it extensively, for every thing they can think of. In most cases, it will not work, or it will not work well, but the point is to try and learn.

I especially do this with my young kids, as I imagine that they will go into a workforce that will probably use AI a lot. I certainly don’t know what careers will exist in the future and how they are going to be affected by AI, but I want them to be very familiar with the usefulness and limitations of AI so that they are well-equipped to make the best decisions for themselves.

As a society, it’s beyond time to start thinking about the allocations of the gains and losses. One thing is clear: if nothing changes, the losses will be allocated to workers that have their job automated. Even at the time of the Luddites, there were already proposals to allocate resources to retrain workers that were losing their jobs to machines. These proposals ended up not being implemented.

But since the time of the Luddites, we have accumulated a lot of knowledge, and we have also improved our communication infrastructure. We can share stories like this one with thousands of people. People can find training online. People have access to cheap AI, even free. We are much better equipped this time around.

Hopefully, this time, we can do better.

References

The main source for this article was the excellent Cautionary Tales podcast episode by Tim Harford, General Ludd’s Rage Against the Machines. I’ve also used the following sources: